Dozens of developers and other pro-business advocates will testify before the D.C. Council on Tuesday to voice concerns about the volume of appeals that have tied up projects in litigation.

They will push for changes to the city’s comprehensive plan that would clarify land use rules regarding planned-unit developments, make it easier for developers to expedite projects and lower the number of legal challenges developers face. Roughly two dozen projects, from the Union Market area to McMillan, have faced legal hurdles despite prior zoning approval.

“As a developer and as someone who works for one of the world’s largest commercial real estate developers in the city, I am very concerned about the frequency with which these appeals are happening,” said Adam Weers, a principal with Trammell Crow Co., one of three companies, along with EYA and Jair Lynch Real Estate, co-developing the 25-acre McMillan site into a mix of office, residential and retail. “There were three in 2015, there were two or three in 2016. There were 17 appeals in 2017. There are four appeals already in 2018.”

The ongoing battle highlights tensions between local developers who want to move forward with more than 6,000 planned housing units and a contingent of residents who believe that those projects, as currently conceived, will displace locals, raise land values and make the city less affordable. Both groups want to change language in the comprehensive plan, which will have a profound impact on the city’s growth over the next 20 years.

“If the land values go up when they put in a development, it forces the people who are there to leave,” said Nick DelleDonne, who is on the steering committee for the D.C. Grassroots Planning Coalition and will testify on Tuesday. “They are not going for better opportunities. They can’t afford to stay there any longer.”

DelleDonne’s organization, according to its website, consists of individuals and organizations “committed to furthering racial, economic and environmental justice by challenging rampant development which contributes to gentrification and displacement of existing residents.” Its membership include representatives of Empower DC, the Committee of 100 on the Federal City, and the Democratic Socialists of DC.

One of the most controversial proposed comprehensive plan changes would provide the Zoning Commission more flexibility on PUDs, making an appeal more difficult to win if the panel doesn’t follow the zoning map to a T. The language reads: “References to representative and specific zone districts in each land use category are intended to provide broad guidance, and are not intended to be strictly followed with respect to determining consistency of a zoning map amendment and/or Planned Unit Development with the Comprehensive Plan.”

Chris Otten, who leads D.C. for Reasonable Development and is the organizer, or backer, of several appeals (and is also a member of the D.C. Grassroots Planning Coalition), said his group isn’t “against development per se.” But he believes the comp plan should provide specific directives for community benefits and amenity packages, identify potential impacts such as displacement and require developers to provide more affordable units.

“We want to strengthen the plan so developers know at the outset when they talk to the Office of Planning, these are things they can expect to talk about, like contributions to infrastructure, contributions to transportation systems, contributions to a community protection fund that protects the community during construction, and real affordability, not just 10 percent,” he said.

Onerous but predictable process

Developers are especially troubled by the appeals that usually follow a lengthy entitlement process — one that requires them to negotiate with city officials and residents on a community benefits package in exchange for zoning flexibility. It is an onerous but predictable process that developers say they have become accustomed when getting projects approved by the D.C. Zoning Commission.

“You get through this and all of the sudden you have to deal with an appeal and a lawsuit,” Weers said.

Perhaps the prime example of this is the controversial $720 McMillan project, which Weers said went through 22 public hearings and well over 200 community meetings.

“We got our entitlements approved in 2015. It’s 2018, I’m still dealing with an appeal,” Weers said. “We had a process. It wasn’t perfect, but it worked. Now we are changing the rules in the middle of the game.”

There are now “thousands of units caught up in these lawsuits and every single one of these projects went through the entitlements process,” he added.

Kirby Vining, treasurer of Friends of McMillan Park, an organization that has fought the McMillan project for many years, said he believes the proposed comp plan changes would give the Zoning Commission “carte blanche” to approve projects and eviscerate a community’s ability to appeal. The friends group has long argued that the city-owned McMillan — entitled for 1 million square feet of medical office space, more than 500 apartments, nearly 150 townhomes and a Harris Teeter — should be scaled back or reimagined as public open space.

“It removes all the checks and balances in the due process that the community has in working with developers,” said Vining, who plans to testify on Tuesday.

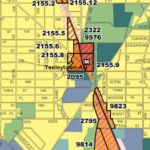

In addition to McMillan, appealed projects that have delayed or quashed by the courts include The Menkiti Group’s 901 Monroe St. NE in Brookland, Foulger-Pratt’s 370-unit Press House at Union District at 301 N St. NE, Kettler’s Market Terminal near Union Market, and Trammell Crow’s Central Armature Works redo.

‘Functional’ process

David Alpert, founder and president of Greater Greater Washington and an organizer of the D.C. Housing Priorities Coalition, said his group is pushing the city to change language in the comprehensive plan that will allow the “PUD process be able function well.”

Alpert’s coalition includes the support of organizations that, on occasion, do not see eye to eye — multiple developers like Menkiti, MRP Realty and Ditto Residential, numerous advisory neighborhood commissions, the Coalition for Smarter Growth, D.C. Fiscal Policy Institute and SEIU 32BJ.

“We want it to be able to function where the Zoning Commission can hear from the community, they can hear from the neighborhood advisory commission, it can determine what community benefits are possible in a project and then it can make a decision saying that the community benefits are sufficient to approve that project and have every project move forward,” Alpert said.

Alpert said the legal challenges have become so pervasive that many developers are no longer pursuing PUDs.

“They are building smaller projects. There are no community benefits,” he said. “There is less housing being created. There’s less affordable housing being created.”

He also said there needs to be clearer language in the comp plan about preserving and creating affordable housing.

“It’s possible to avoid displacement in a way that is in partnership with the development community,” he said.