About 100 advocates of turning White Flint into a transit-oriented urban area crowded into a back room at Seasons 52 restaurant one evening last week to talk about making Rockville Pike more hip.

The location was appropriate. The restaurant is in a block of newer buildings, near the White Flint Metro stop, that includes an Arhaus Furniture store and a Whole Foods Market. The stretch is linked together by landscaped streets and sidewalks.

Across Rockville Pike is White Flint Mall. Built in the 1970s, the mall’s empty stores and surface parking lots are exactly what many people at the Jan. 29 networking event wanted to replace.

Advocates for urban development built around public transportation say White Flint can be a model for similar growth elsewhere in Montgomery County and in the nation as a whole. To accomplish that, groups that sprang up around a sector plan a few years ago are redoubling their efforts and drumming up support for their vision.

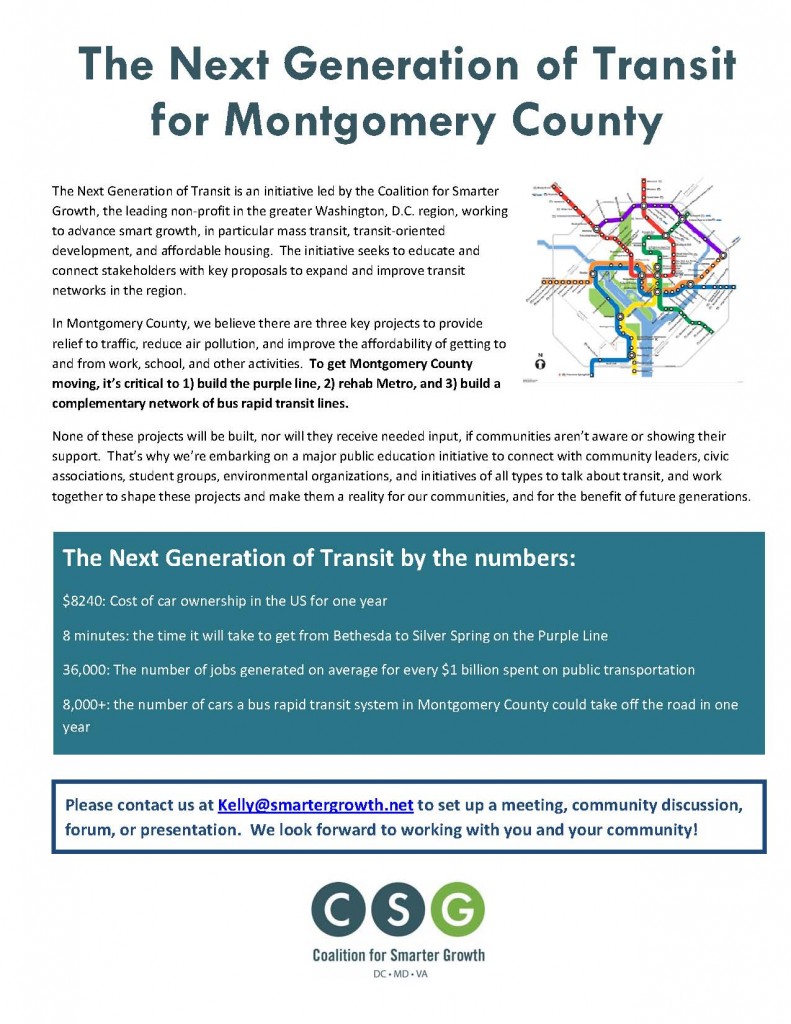

The Coalition for Smarter Growth, founded in 1991, pushes for walkable communities around the District, connected by high-quality transit, said Kelly Blynn, manager of the coalition’s Next Generation of Transit campaign.

“We are focusing a fair amount on White Flint, which we see as an important model for how you need to plan land-use planning with transit planning,” she said.

The White Flint Sector Plan, which set guidelines for development and land use in the area, was adopted in 2010. Now, Blynn said, the area is entering another critical phase as individual developers submit building plans and government officials consider creating new transit options.

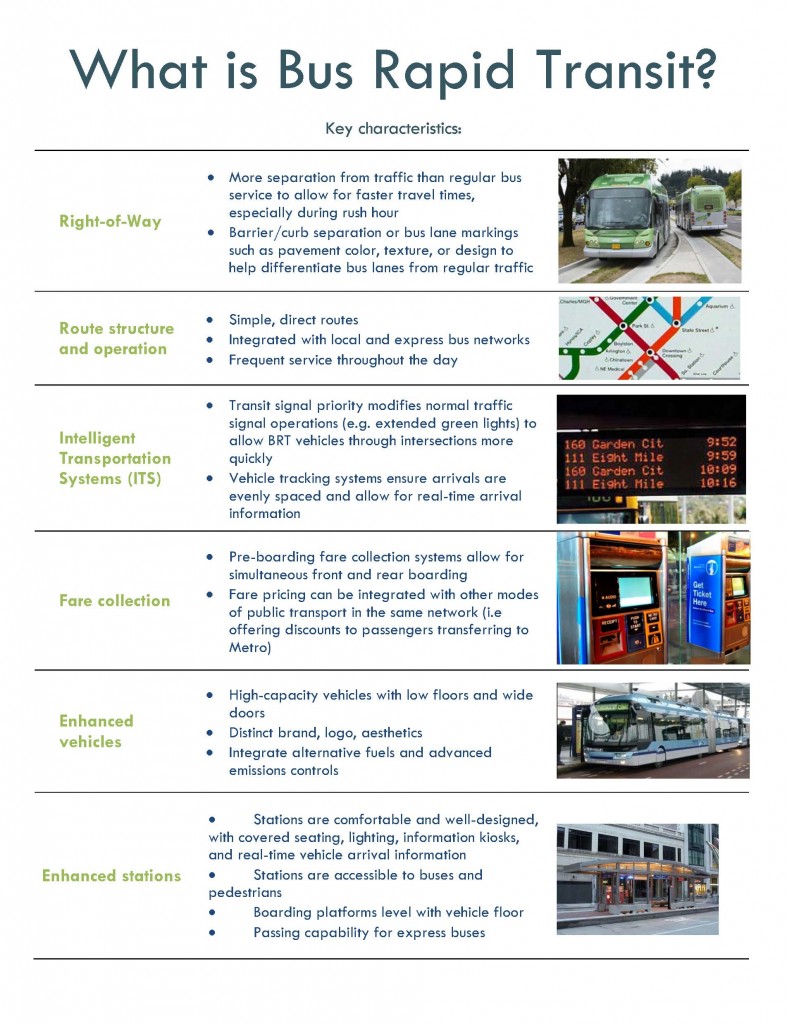

Officials are considering putting a rapid bus transit system in the area, which Blynn said would tie the communities on Rockville Pike together.

“We think it’s a complementary system for other programs that are underway,” such as upgrades to the Metrorail system and the Purple Line, she said.

Lindsay Hoffman, executive director of the organization Friends of White Flint, said the sector plan was the big picture and the vision for White Flint, but advocacy groups still play a role in making sure that individual development projects fit into the plan.

“Every little site and development and piece of land has to go through [its] own process very similar to the sector plan process,” she said. “We still want to generate energy, generate positivity and generate a collaborative framework.”

Hoffman said Friends of White Flint helped get community groups, residents and developers together relatively early in the sector-plan process, which offered a venue for people to give feedback on ideas for the area rather than waiting until developers submitted plans to the planning board further down the line.

“By having that collaboration early on, we were able to overcome [many] people’s concerns,” she said.

Now, Hoffman wants to get people involved in the early stages of discussions about plans for transit projects and funding transportation improvements.

“We’re going to work on stimulating some energy among community residents who are interested in it to speak out,” she said.

The White Flint Partnership, a group of major property owners, also formed around the sector plan development process, but is planning to stay active.

Francine Waters is the senior managing director of transportation and smart growth for Lerner Enterprises, one of the developers working on plans to demolish most of White Flint Mall and replace it with a mixed-use town center. She also serves as executive director of the White Flint Partnership.

Waters said the partnership plans to work with groups such as Friends of White Flint to keep people up-to-date on the status of development projects and infrastructure improvements. She also hopes to bring in urban planning experts for a speaker series.

Rod Lawrence, a partner at JBG Companies who helped found the White Flint Partnership, said the group stayed together to make sure the plan doesn’t stray from its original intent. It also helps bring attention and resources to the area, he said.

“We’re trying accelerate the infrastructure development [and] encourage the right type of redevelopment,” Lawrence said.

JBG developed North Bethesda Market, which houses Seasons 52, and is planning a second phase of the mixed-use development project, dubbed North Bethesda Market II.

Lawrence sees the White Flint Partnership as a precursor to some kind of business improvement district or place-management group to bring attention to the area and encourage public-private cooperation.

The group needs “people — citizens, businesses, public officials, everybody — coming together to make sure that you build momentum and keep momentum for the plan,” he said.