Rockville Pike can be an unpleasant place to walk. The six-lane, highway-like road along the strip malls and parking lots of White Flint is heavy on traffic and light on the type of streetscaping in Bethesda Row or even Woodmont Triangle. Montgomery County and the developers behind the many mixed-use projects planned for the corridor would like to see that change. On April 27, the group leading the charge for smart growth initiatives will offer a glimpse of what that future might hold.

Category: News

The North-South Divide

Battle lines are forming over the north-south transportation corridor in Northern Virginia. Backers say it would serve a growing population and stimulate economic development. Foes say the state has more urgent priorities for spending $1 billion or more.

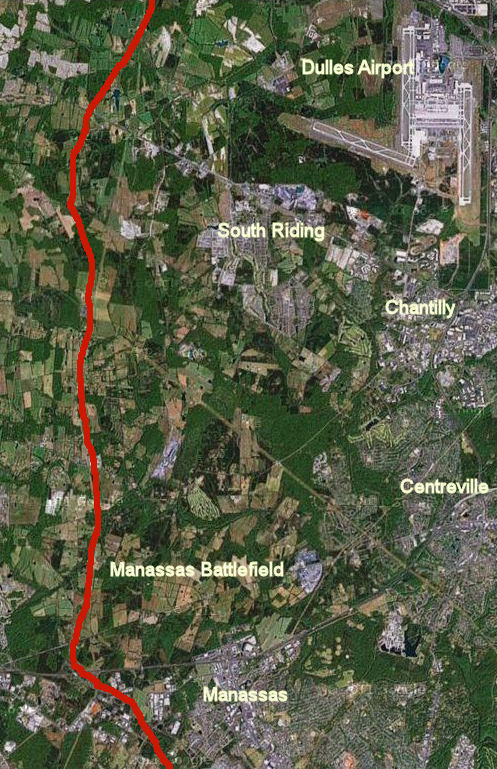

Red line shows approximate route of the North-South Corridor where it runs through the Manassas Battlefield and extensive farmland.

Northern Virginia, we hear over and over, is one of the most congested regions in the nation – perhaps the most congested. Even with new mega-projects coming on line like interstate express lanes and the rail-to-Dulles Metro service, the list of transportation needs seems endless. Most improvements under consideration are designed to ameliorate the traffic gridlock that grips the region now. But one particular cluster of projects zooming through the bureaucratic approval process is designed to address traffic congestion that is forecast to be a problem… in 2040.

In 2011, the Commonwealth Transportation Board (CTB) added the so-called North-South Corridor west of Dulles International Airport to its list of strategically important Corridors of Statewide Significance (CoSS), a designation that gives priority funding to projects within the corridor. It was the first time the CTB had added a new corridor not based upon an existing Interstate or rail line. Fast-tracking the project, the McDonnell administration has held public hearings and plans to present findings regarding a specific route and the cost to build a limited access highway this month.

Backers say Northern Virginia needs a north-south corridor – in particular, a limited access highway known in different configurations as the Tri-County Parkway or Bi-County Parkway — to accommodate the region’s fast-growing population and employment, and also to promote freight cargo-related economic development around Dulles International Airport.

“If you look at the population projections of the [Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments] and the Commonwealth of Virginia, you see a major percentage of future growth in Northern Virginia does occur in this corridor and points west,” says Bob Chase, president of the Northern Virginia Transportation Alliance. “Loudoun and Prince William counties will add a couple hundred thousand people over the next 20 to 30 years.”

But skeptics describe the project as a wildly speculative endeavor that might enrich big landowners whose properties could be developed but otherwise do little to address Northern Virginia’s most pressing concerns. In particular, they say, Northern Virginia growth patterns in the 1990s and 2000s have zero predictive value for the future.

“The world has changed. Our population is older and is downsizing their homes. Empty nesters and younger workers want to live closer to jobs and transit, and in more urban places,” says Stewart Schwartz, executive director of the Coalition for Smarter Growth (CSG). “Moreover, the region has far more pressing needs serving existing population centers and addressing existing congestion. We need every dollar to fix existing commuter routes like I-66.”

Funding the north-south corridor, says Schwartz, would be “a misallocation of scarce resources.”

Only a year ago, the point seemed moot. Virginia was running out of state funds for new highway construction projects. But the north-south corridor controversy is sure to flare now that the General Assembly and Governor Bob McDonnell are close to approving a restructuring of transportation taxes that is expected to raise $800 million a year statewide for new transportation spending. Projects that had been pushed to the back shelves suddenly look fundable.

$2 Billion dollar project?

Northern Virginia’s major transportation arteries – Interstate 95, Interstate 66 and the Dulles Toll Road – all converge on the I-495 Capital Beltway or Washington, D.C., itself. Over the decades, population growth, job growth and development have followed those pathways out from the urban core. North-south arterials have been built to connect that growth, including the Fairfax County Parkway in the center of Fairfax County, and Rt. 28, farther west. The North-South corridor would represent a fourth such arterial but it would serve hypothetical future transportation demand, not a demand that exists at present.

Although the final plan has not yet been published, the North-South corridor likely will follow a path something like this:

- Apexct its southern terminus the highway will start at Interstate 95 in Prince William County. It will follow the existing Rt. 234, which becomes a partially limited access highway west of Manassas.

- The highway will proceed north across I-66 along the western boundary of the Manassas Battlefield and run parallel to Pageland Lane through miles of farmland, in areas zoned for low density — the so-called Tri-County Parkway.

- The highway will incorporate Loudoun’s expansion of Northstar Boulevard, crossing another stretch of undeveloped land, where it will connect to Belmont Ridge Road until it reaches the northern terminus at Rt. 7.

Because corridors of statewide significance are designated multimodal corridors, not just highways, the north-south corridor plan could include other components such as tolled express lanes and, in theory, Bus Rapid Transit, although there is unlikely to be much demand for mass transit in a rural area far from major job centers. Also, the McDonnell administration is studying the idea of linking the proposed highway to the western approaches of Dulles airport and upgrading Rt. 606, which runs along the western edge of the airport. These improvements would open property on the west side of the airport for commercial development.

Smart growth groups like the Coalition for Smarter Growth and the Piedmont Environmental Council view the north-south corridor as the same as an Outer Beltway proposal that belly-flopped more than a decade ago, with the main difference being that the McDonnell administration seems willing to build it piece by piece rather than all at once. The original plan for the Outer Beltway was to continue north, bridging the Potomac River and hooking up with a major Maryland arterial, opening vast tracts of relatively inaccessible land for new subdivisions and shopping centers. Maryland officials have made it clear that they have no interest in such a collaboration but the Virginia Department of Transportation is footing the bill in a separate study to examine the feasibility of building another Potomac crossing at an unspecified location.

The Office of Intermodal Planning and Investment (OIPI) is scheduled to present its recommendations to the CTB regarding the routing and corridor improvements, says Dironna Belton, OIPI policy and program manager. The OIPI will not make its cost estimates available until then.

Schwartz with the CSG guesstimates that the north-south corridor would cost a minimum of nearly $1 billion — figure $19 million per mile for 50 miles — only a small portion of which could be paid for by tolls. Some of the highway would follow the existing Rt. 234, he says, but construction work on an operating road is very expensive. Throw in some interchanges and the cost of connecting the highway to Dulles airport, he says, and the project could approach $2 billion.

Growth Projections

The argument for a north-south corridor is based upon the proposition that jobs and population growth will continue booming on the western edge of the Washington metropolitan region. That case is buttressed by forecasts made by the Weldon Cooper Center for Public Service’s Demographics & Workforce Group, which serve as the basis for state and local government planning purposes.

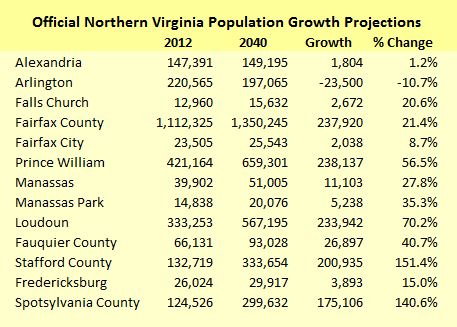

Here are the Weldon Cooper projections for the year 2040, listing jurisdictions in rough order of their proximity to the Washington urban core.

According to the Weldon Cooper projections, jurisdictions in the urban core like Arlington and Alexandria will see no growth – or actually shrink. Following the radius out from the core, Fairfax County will continue to see substantial growth in absolute numbers but only moderate growth as a percentage of its already-large population. The bulk of the population growth will occur in outer-ring counties, especially Loudoun and Prince William but also, traveling down Interstate 95, Stafford and Spotsylvania.

In just Loudoun and Prince William counties and Manassas, the jurisdictions directly served by the north-south corridor, the population is expected to grow by nearly 500,000 by 2040.

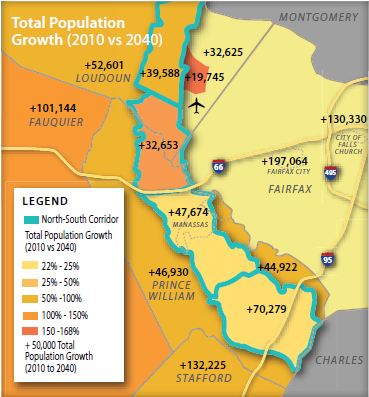

In its study of the north-south corridor, the McDonnell administration has embraced the forecast of booming exurban growth. “Nearly 700,000 jobs, 800,000 people, and 300,000 new households are expected to join [Northern Virginia] over this 30-year timeframe,” states an OIPI newsletter. “Much of this future growth is expected to occur within Loudoun and Prince William Counties. Larger portions of the new employment and population growth are expected within the North-South corridor area.”

According to maps published in the OIPI newsletter, population in the corridor study area itself will increase by 190,000 and jobs by 127,000. Population in areas immediately to the west will grow by 230,000 more.

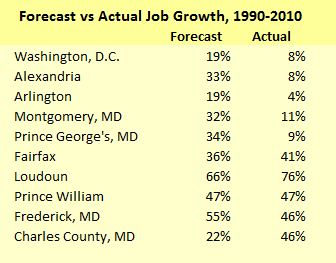

Chase with the Northern Virginia Transportation Alliance argues that the growth projections actually might be conservative. In a recent email, he distributed a chart, based upon National Capital Region Transportation Planning Board data, comparing a 1990-to-2010 job-growth forecast made for the Washington region with actual performance. Urban-core jurisdictions like Washington, Alexandria and Arlington under-performed the forecast by a wide margin while outer jurisdictions tended to out-perform the forecast. “These trends are expected to continue for decades to come,” he wrote.

In the battle over a proposed outer beltway a decade ago, which would have run more or less the same route, the Piedmont Environmental Council had warned that building the beltway would generate a population explosion, says Chase. “We didn’t build the corridor but the people came anyway.”

The idea that building roads causes population growth to occur that would not otherwise is wrong, Chase says, particularly in places like Northern Virginia with a strong economy and people moving in from all around the country.

Creating a north-south corridor makes sense, he says. As he wrote in the email cited above: “Most of the region’s workforce lives outside the Beltway and employers are moving closer to their workers. Moving jobs closer to where people live is more efficient than moving people (longer distances) to jobs. It reduces commutes and creates a better balanced, stronger regional economy.”

Inflection Point

A big problem with the Weldon Cooper population projections and all the forecasts based upon them is that they extrapolate past trends into the future. There is reason to question whether Northern Virginia can replicate the population and employment growth of the go-go 2000s during the austere 2010s.

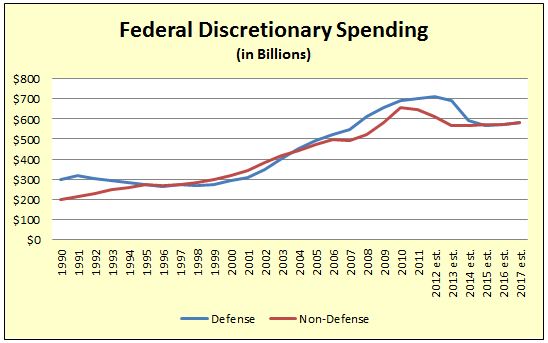

The terrorist attack on 9/11/2001 precipitated a decade-long growth in spending on defense, intelligence and homeland security, with much of the money going to federal agencies and contractors in Northern Virginia. With Washington adither over unsustainable budget deficits, however, the main question today is by how much defense spending will shrink. Likewise, spending on discretionary (non-entitlement) domestic spending is expected to level off, according to the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) data show below. While federal spending is not likely to collapse any time soon, it won’t provide the jet fuel for Northern Virginia’s growth that it has in the past.

Not only is population and employment growth likely to slow, smart growth advocates contend that the pattern of that diminished growth is shifting dramatically away from the peripheral counties of the Washington MSA back toward the urban core.

Many urban economists believe that the forces impelling metropolitan growth to green-fields on the periphery have petered out or even reversed themselves. That doesn’t mean there won’t be any job or population growth in places like Loudoun and Prince William, but it does suggest that growth could fall far short of projections based on past trends.

Major economic and demographic shifts are transforming growth patterns across America. Most notably, the cost of automobile ownership is outstripping the rate of inflation and household incomes. Over the past decade (2003 to 2013), the Internal Revenue Service deduction for business travel, a good proxy for the cost of owning and operating a car, surged 57% to 56.5 cents per mile, far faster than the 26% increase in the consumer price index over the same period.

There is good reason to believe that the cost of ownership will continue to rise. Global supply and demand forces will continue to push the cost of gasoline higher. Interest rates, a critical factor for automobile financing, can hardly get any lower and likely will climb. Federal fuel economy standards will save on gasoline costs but increase the cost of purchasing cars — a 2012 study by the American Automobile Association indicated that 122,000 licensed drivers in Virginia, or 1.9%, would be priced out of the market. Meanwhile, automobiles are evolving into mobile communication and connectivity hubs that add tremendous functionality but also push up the price. While the cost of driving is increasing, incomes are stagnating for the bottom 80% of income earners. Assuming the laws of economics still hold, Americans will adapt to the higher cost of automobile ownership by driving less.

That economic trend dovetails with major demographic trends. Two-thirds of all households today consist of singles, childless couples, or empty-nesters, and that proportion will rise over the next 20 years, Christopher Leinberger , a real estate developer, Brookings Institution fellow and author of “The Option of Urbanism,” has argued. Those households don’t need a big suburban yard where Little Johnny can run and play. They prefer smaller accommodations that require less maintenance and offer a variety of transportation options. Indeed, Leinberger says, there is a huge housing surplus in what he terms the “drivable suburbs” and a pent-up demand for what he calls “walkable urbanism” where inhabitants can meet many of their daily needs by walking, biking or riding mass transit.

The evolving priorities are most evident among Millennials, the rising generation of 20- to 30-year-olds, who appear to be less enamored with automobiles than their parents were. In 2008, according to the Federal Highway Administration, only 46.3 percent of potential drivers 19 years old and younger had drivers’ licenses, compared to 64.4 percent in 1998. Similarly, drivers in their twenties drove 12 percent fewer miles in 2009 than twenty-somethings did in 1995. In big cities, many Millennials are abandoning the idea of car ownership and flocking to rental services like ZipCar and ride-sharing services like SideCar and Lyft.

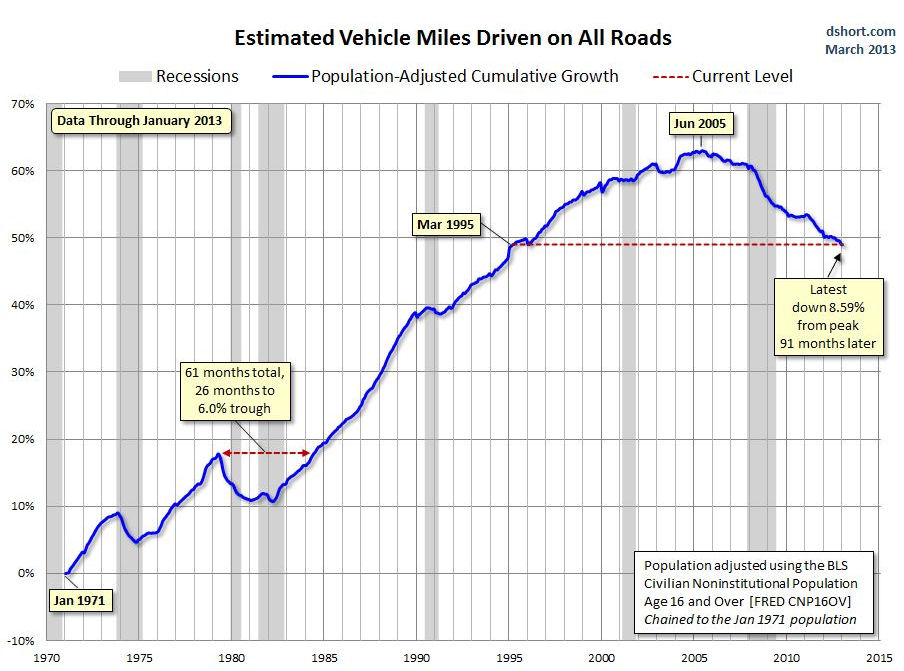

Consistent with these trends, the 12-month moving average of Vehicle Miles Traveled (VMT) plateaued in 2006 around 3 trillion miles, according to Federal Highway Administration data, and has dipped since then. Adjust for population growth, as seen in the chart below, and the decline is striking.

Graphic credit: Business Insider.

In the Washington region, developers are pouring billions of dollars into re-developing the District, close-in suburbs like Arlington, and even middle-band suburbs like Fairfax County. D.C.’s population increased by 30,000 over the previous 27 months, the Census Bureau reported in December 2012. Arlington planners, who count some 1,380 housing units under construction at present, project that 36,000 residents will move to their county by 2040 — diametrically opposite to Weldon Cooper’s prediction forecast that the jurisdiction will shed 23,500 people.

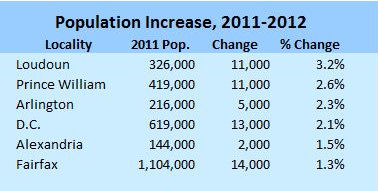

Here is the breakdown for population growth in 2012. At this point Loudoun and Prince William, which are working off a large inventory of houses and lots from the recession, are on pace with the Weldon Cooper projections. But Arlington and D.C. are coming on strong.

Meanwhile, Fairfax County is the sleeping giant. Nowhere is the shift in human settlement patterns more visible than at the 10 Metro stops planned for the Silver Line. Literally tens of millions of square feet of walkable, mixed-use development are planned for Metro stations along the Dulles Corridor. Fairfax County is undertaking a massive, multibillion-dollar transformation of Tysons from the prototypical auto-centric suburban office district into a pedestrian-friendly community. The addition of a strong residential component to Tysons alone could absorb between 20,000 and 40,000 new inhabitants by 2040.

Alternate investments

Given the pent-up demand for transit-oriented development and the massive resources committed to building it in Northern Virginia, diverting resources to the North-South corridor makes no sense, contends Morgan Butler, senior attorney for the Southern Environmental Law Center (SELC). Investing in the Silver Line so Tysons can be the center of growth while building a highway that facilitates sprawl are mutually contradictory aims, he says. Transit-oriented development represents the future, he says, and state and local authorities should focus limited resources on making it work.

Northern Virginia has many transportation needs that are urgent right now, much less three decades from now. Just one example: A recently issued Environmental Impact Statement found, for example, that nearly half of a 25-mile stretch of Interstate 66 outside the Capital Beltway operates at a Level of Service E or F (worse than free-flow conditions) during morning rush hour. Nearly two-thirds are deficient during the afternoon rush hour.

What kind of traffic relief could Northern Virginia buy with the $1 billion or more proposed for the Tri-County Parkway?

A coalition of smart-growth and conservation groups has published an alternative to the Tri-County Parkway that would not only protect Loudoun and Prince William farmland and steer traffic away from the Manassas Battlefield Park but ameliorate congestion that afflicts commuters here and now. States their “Updated Composite Alternative”:

Our alternative is designed to address the much greater need for east-west commuter movement and to provide for dispersed, local north-south movement for current and future traffic. Access to Dulles is provided by the completion of upgrades to Route 28 from I-66 north, improvements to the I-66 corridor, and upgrades to the Route 234/Route 28 connection and Route 28 on the east side of the Cities of Manassas and Manassas Park. The composite set of connections is designed to improve traffic movement throughout the area, benefitting more travelers and trip types than would the single large north-south highway proposal.

The document does not contain a cost estimate for the alternative projects, which includes mass transit and lots of local road fixes, so it’s not clear if the proposals constitute an apples-to-apples comparison with the proposed north-south corridor improvements. What is clear is that there is no lack of pressing projects competing for that $1-$2 billion.

The Air Cargo Push

Backers of a north-south corridor cite a second justification for the Bi-County Parkway: By improving access to Dulles International Airport, a highway would promote warehouse and logistics investment around Dulles Airport and even in Prince William County.

The Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority (MWAA) plans to develop 400 acres of airport property on Route 606, while Loudoun County is promoting 500 acres on the north-south corridor for cargo expansion, according to a December 2012 presentation made by Garrett Moore, then-district administrator for Northern Virginia. VDOT is conducting an environmental assessment for widening Rt. 606 on the western edge of Dulles’ property and a variety of other projects to improve western access to the airport.

“My gut tells me that Dulles in terms of cargo is about where we were with passengers in 1982. In those days, … there was very little passenger activity,” says Leo Schefer, president of the Washington Airports Task Force. But passenger service did take off. Dulles now is one of the busiest airports in the country and an economic engine of Northern Virginia. Schefer sees a parallel process underway with air freight. The established air cargo gateways are becoming more congested and more expensive to operate. The big logistics companies can cover their bets, he suggests, by establishing a presence at Dulles, which has enormous expansion potential and superior operating economics.

Schefer concedes that cargo-related development is not a sure thing. Unlike passenger service, in which airlines respond to rising traffic volume, “air cargo is more of an economic development exercise.” Northern Virginia economic developers need to persuade the big logistics companies to use Dulles as a strategic gateway where they can consolidate operations. That won’t be the easiest sell because the Washington region is not itself a huge market for air cargo. “We don’t produce much here besides paper,” he quips.

Northern Virginia is too expensive for the manufacturing sector, a major customer of air freight. However, Schefer sees that changing as new super high-tech manufacturing technologies are deployed and increasingly automated manufacturing processes rely upon fewer, more highly skilled employees. That kind of manufacturing could thrive in the region, he suggests, especially if manufacturers could avail themselves of superior air-freight access.

Be that as it may, Dulles has the real estate to accommodate large warehouses. “Logistics companies will want to see better truck connections,” Schefer says. “That’s where the north-south corridor comes in: A highway would provide superior access to markets to the west and south.”

Local economic developers view the situation similarly. “We view [the corridor] as an asset,” says Brent Heavner, marketing and research manager for the Prince William County Department of Economic Development. “One of the advantages of having better north-south transportation capacity is the market it opens up for industrial, warehouse and distribution users” in Prince William County, particularly the western county. “Right now those operations are at a disadvantage due to the circuitous route they have to move their freight to reach Dulles.”

A beefed-up air freight operation at Dulles might find itself competing with Richmond International Airport (RIC), which also has positioned itself as an air cargo handler. At this point, however, Dulles’ air-cargo ambitions have not made much of an impression on RIC. It’s not something airport management has studied, says Troy Bell, director of marketing and air service development. “We’re not anti-Dulles. But we have capacity and a very capable field.”

Schwartz remains skeptical of the economic-development argument. “Dulles is pushing its dreams on the rest of us. … They’ve justified the corridor by cargo growth at Dulles Airport. We think that’s a red herring. Air freight is a tiny percentage of total freight traffic.” While Dulles boosters have been promoting the north-south corridor, he adds, the air freight companies themselves have been conspicuously quiet.

There may be sufficient locally generated traffic demand to justify four-laning Rt. 606 on the west side of Dulles, a project that would cost $50 million, Schwartz says. But the Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority (MWAA) wants eight lanes and four interchanges, which could bump the project up to $300 million. “They’re asking for the taxpayer to pay for the expansion of Rt. 606. Why shouldn’t they pay for it?”

The way forward

In sum there are several imponderables the state needs to consider before putting money into the north-south corridor:

- Federal budget. Will the federal government deal with chronic deficits and a mounting national debt by cutting defense and discretionary spending, the lifeblood of the Washington metropolitan economy, and what impact would a spending slowdown have on population and job growth in Northern Virginia, particularly in the area served by the north-south corridor?

- End of sprawl. Do economic and demographic trends portend an historic shift in the pattern of growth and development in the Washington region, away from the growth frontier served by the north-south corridor and back toward walkable urbanism served by mass transit?

- Dulles air freight. Does Dulles air-freight traffic have a realistic shot at growth, and how significant is the economic impact of that growth?

- Alternative investments. How much will North-South corridor improvements cost, and how else could funds be deployed to mitigate congestion and create economic value?

Anyone can say anything. Anyone can make unsubstantiated claims. As Nassim Taleb, author of “The Black Swan” and “Antifragile” observed, however, players with “skin in the game” — with something to lose if they’re wrong — deserve to be taken more seriously than outside pundits and prognosticators.

One option for the commonwealth would be to solicit bids to build the Tri-City Parkway and other corridor improvements by means of a public-private partnership, in which private-sector partners would invest their own money. Private investors, unlike parties with a political or ideological axe or something material to gain or lose, would have every incentive to develop realistic projections for the key drivers of traffic volume and toll revenue: population, employment and air-freight growth. If corridor improvements create sufficient economic value, it should be possible to pay for the project with toll road revenue. If the demand is lacking or takes too long to materialize, as happened to private investors in the Dulles Greenway, private players will pay the cost of their miscalculation with their own money — not the taxpayers’.

The McDonnell administration’s experience with the U.S. 460 project between Petersburg and Suffolk, designed to serve a projected increase in port-related traffic, is instructive. Soliciting bids from three construction consortia, the Office of Public Private Transportation Partnerships discovered that the private sector was willing to fund only a tiny portion of the project. Demand for the facility would be more uncertain and take longer to materialize than originally anticipated. In a controversial decision, the administration chose to commit more than $1 billion in public funds anyway in the hope that the highway would attract major industrial investment.

Soliciting public-private partnership proposals for the North-South Corridor could yield similarly useful information. How much of their own money would investors bet on the prospect of massive population and employment growth in eastern Loudoun and western Prince William? Investor willingness to fund the project would eliminate grounds for complaining that the project is diverting state funds from Northern Virginia’s other transportation needs. Similarly, the unwillingness of investors to put their own money into the project without a massive state subsidy would be a clear sign that the anticipated benefits are either too meager, too chancey or too slow to materialize to warrant investment at this time.

Images courtesy of Bacon’s Rebellion

Why Tolls Will Be Waived On One Virginia Highway This Weekend

Nearly five months after opening, the operators of the 495 Express Lanes are struggling to attract motorists to their congestion-free toll road in a region mired in some of the worst traffic congestion in the country.

Transurban, the construction conglomerate that put up $1.5 billion to build the 14-mile, EZ Pass-only corridor on the Beltway between the I-95 interchange and Dulles Toll Road, will let motorists use the highway free this weekend in a bid to win more converts.

“It takes a lot of time for drivers in the area to adapt to new driving behaviors. A lot of us are kind of stuck on autopilot on our commutes. That trend might continue for a while, too,” said Transurban spokesman Michael McGurk.

Light use of HOT lanes raises questions

McGurk says some drivers are confused about the new highway’s many entry and exit points. Opening the Express Lanes for free rides this weekend will let motorists familiarize themselves with the road, he said.

After opening in mid-November, the 495 Express Lanes lost money during its first six weeks in business. Operating costs exceeded toll revenues, but Transurban was not expecting to turn an immediate profit. In the long term, however, company officials have conceded they are not guaranteed to make money on their investment. Transurban’s next quarterly report is due at the end of April.

To opponents of the project, five months of relatively light traffic on Virginia’s new $2 billion road is enough to draw judgments. Vehicle miles traveled (VMT) has not recovered since the recession knocked millions out of work and more commuters are seeking alternatives to the automobile, according to Stewart Schwartz, the executive director of the Coalition for Smarter Growth.

“They miscalculated peoples’ time value of money. They overestimated the potential demand for this road,” said Schwartz, who said the light use of the 495 Express Lanes should serve as a warning.

“We should not have rushed into signing a deal for hot lanes for the 95 corridor, and we certainly shouldn’t rush into any deal on I-66,” he said.

Transurban is counseling patience.

“We’re still in a ramp-up period. You’ve probably heard us say that since the beginning, too, but with a facility like this it’s a minimum six months to two years until the region falls into a regular pattern on how they’re going to use this facility,” McGurk said.

In its first six weeks of operations toll revenues climbed on the 495 Express Lanes from daily averages of $12,000 in the first week to $24,000 in the week prior to Christmas. Traffic in the same period increased from an average of 15,000 daily trips to 24,000, according to company records. Despite the increases, operating expenses still outstripped revenues.

It is possible that traffic is not bad enough outside of the morning and afternoon rush hours to push motorists over to the EZ Pass lanes on 495.

“It may also show that it takes only a minor intervention to remove enough cars from the main lanes to let them flow better,” said Schwartz, who said the 14-mile corridor is simply pushing the bottleneck further up the road.

Even Transurban’s McGurk says many customers who have been surveyed complain that once they reach the Express Lanes’ northern terminus at Rt. 267 (Dulles Toll Road), the same terrible traffic awaits them approaching the American Legion Bridge.

Express Lanes a litmus test for larger issues

The success or failure of the 495 Express Lanes will raise one of the region’s most pressing questions as it looks to a future of job and population growth: how best to move people and goods efficiently. Skeptics of highway expansions, even new facilities that charge tolls as a form of congestion pricing, say expanding transit is cheaper and more effective.

“An approach that gives people more options and reduces driving demand through transit and transit-oriented development may be the better long-term solution. But we’ve never had these DOTs give us a fair comparison between a transit-oriented investment future for our region and one where they create this massive network of HOT lanes,” said Schartz, who said a 2010 study by the Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments pegged the cost of a tolled network of 1,650-lane miles of regional highways at $50 billion.

Transportation experts say a form of congestion pricing, either tolled lanes or a vehicle miles traveled tax, may be part of a regional solution to congestion. The public, however, needs to be explained why.

“As long as the majority of system remains non-tolled and congested then you are not going to solve the problem,” said Joshua Schank, the president of the Eno Center for Transportation, a D.C.-based think tank.

“Highways in this region are drastically underpriced. People are not paying enough to maintain them and they certainly are not paying enough to pay for the cost of congestion. The American people have been sold a bill of goods because they have been told that roads are free. Roads cost money,” he added.

The 495 Express Lanes are dynamically-priced, meaning the tolls increase with demand for the lanes. The average toll per trip in the highway’s first six weeks of operations was $1.07, according to Transurban records. As motorists enter the lanes they see signs displaying how much it will cost to travel to certain exits, but no travel time estimates are displayed. “It is important to be very clear to drivers about the benefit of taking those new lanes, and I am not sure that has happened so far,” said Schank, who said it is too early to conclude if the Express Lanes are working as designed.

“It’s hard to know if it works by looking whether the lanes are making money. I don’t know if that is the right metric. It’s the right metric for Transurban, but it’s not necessarily the right metric from a public sector perspective,” he said. “The real metric is to what extent does it improve economic development and regional accessibility, and that’s a much harder analysis that takes some real research and time.”

Photo courtesy of Transportation Nation

Transit Advocates Pushing For Support In Bus Rapid Transit Debate

Transit advocates are going on the offensive after the Montgomery County Planning Board expressed some reluctance toward the idea of wiping out a lane of regular Rockville Pike traffic for Bus Rapid Transit-exclusive lanes.

That idea, presented in Planning Staff’s Draft Countywide Transit Corridors Functional Master Plan a few weeks ago, almost immediately drew skepticism from residents and Planning Board members.

The D.C. based Coalition for Smarter Growth sent an email to supporters on Thursday asking people in favor of the BRT-dedicated lane to email Planning Board members ahead of next week’s second meeting on the Draft, set for Thursday, April 4.

In it, CSG asks “Will we continue to place cars above all else in the decisions we make, or will we begin to make a shift towards providing better options for people than sitting in traffic?”

Montgomery’s proposed Rapid Transit System can transform travel in our county, but there are a number of potential hurdles. This week we are approaching one of those hurdles and we need your voice.

A key part of the Rapid Transit System’s recipe for traffic relief is giving priority to rapid transit vehicles over cars where it’s the most efficient use of our roads. It’s also a principle that has been part of Montgomery’s general plan since 1993. But in hearings last week, some members of the Planning Board appeared to waver in their commitment to this key principle.

As the hearings pick up again, we need to make sure that Montgomery residents are voicing their support for lane priority so that we don’t end up with a watered-down system that makes no impact on reducing traffic.

County staff are hard at work calculating which roads would be the best fit for a high-quality, reliable Rapid Transit System to connect our communities and complement Metro and the coming Purple Line.

Priority lanes for transit aren’t a new idea. 20 years ago, the 1993 Master Plan’s transportation section stated we should “Give priority to establishing exclusive travelways for transit and high occupancy vehicles serving the Urban Ring and Corridor.”

Communities committed to prioritizing transit, like Arlington, Bethesda, and many others have seen success in relieving traffics, providing better options for people to get around, and improving quality of life. But last week’s Planning Board discussions indicate that they may be wavering on that fundamental point, and that they may need some convincing that prioritizing transit where it’s most efficient is the right decision for the county.

Without a commitment to that concept, building a high quality Rapid Transit System could be very difficult. The debate really comes down to this: How will we share the road? Will we continue to place cars above all else in the decisions we make, or will we begin to make a shift towards providing better options for people than sitting in traffic?

Many are against the proposal to make three-lane northbound and southbound Rockville Pike from the Beltway to the D.C. line into two lanes of regular traffic with a lane that would be dedicated exclusively to the BRT system, perhaps with stations and boarding areas in the median.

Residents have complained that the BRT system won’t be convenient enough for them to use for non-commuting purposes and that ridership would not offset the traffic impacts of reducing three lanes of already clogged traffic to two.

The Planning Board sent Planning Staff back to the drawing board in order to find new language for the Draft that would put drivers at ease.

“To me, this document screams that we don’t care what happens to drivers and I’m not comfortable taking that position,” Planning Board Chair Francoise Carrier told lead Planning Staff member Larry Cole during the first worksession on March 18.

Press Statement: Maryland Senate Passes Transportation Funding Bill

In response to the Maryland Senate’s vote in favor of the transportation bill (HR 1515), Coalition for Smarter Growth Executive Director Stewart Schwartz issued the following statement: “The Maryland Senate made a winning decision today for Marylanders. Passing the transportation bill means desperately needed transit projects like the Purple Line, Baltimore’s Red Line and MARC upgrades can go forward. Transit projects like these are top priorities to give Marylanders affordable transportation choices, relief from numbing traffic, and cleaner air.”

Activists say transit priority essential to traffic relief

As Montgomery County planners tweak wording in a draft transit master plan, some activists say prioritizing the 10 corridors and 79 miles of proposed future bus rapid transit is essential to easing traffic gridlock.

The county’s planning board on March 18 rejected the first draft of the Countywide Transit Corridors Functional Master Plan, sending it back to the staff to soften language and explain why the plan recommends giving transit priority over cars and drivers.

The planning board is scheduled to discuss the updated draft at 9 a.m. April 4.

Action Committee for Transit President Tina Slater expressed disappointment that debate over transit priority has delayed the plan’s progress, even if only for a few weeks.

Unlike the county’s Ride On bus system, which is mired in the same traffic that gridlocks cars, BRT will give residents an option they never have had before by moving riders more rapidly in dedicated lanes, she said.

The population of Montgomery is expected to increase by 205,759 people by 2040, according to a Montgomery County Demographic and Travel Forecast, based on a 2012 Metropolitan Washington Council of Government report. Slater questioned how even more residents will get around if the county does not prioritize transit.

“We are going to have a major transportation problem on our hands if we don’t do something now,” she said.

Stewart Schwartz, executive director of the Coalition for Smarter Growth, saw the planning board’s delay as doing its homework to ensure the right routes and dedicated service are recommended.

However, Schwartz said his organization feels there are more corridors poised for dedicated lane service than the staff recommended.

During the discussion on March 18, Planning Commission Chairwoman Francoise M. Carrier said she quarreled with the plan’s “categorical statements that transit gets priority all the time everywhere.”

Carrier argued that any priority should be expressed in more nuanced language.

Acting Planning Director Rose Krasnow said that under the existing procedure, roads get priority, all the time, everywhere, which has greatly harmed the quality of life.

Planning Board Commissioner Casey Anderson cautioned watering down the language.

If the board were discussing a rail line, it would not debate whether it was fair to give it priority over other traffic, he said.

But both the problem and advantage of BRT is that it can operate in a myriad of ways — dedicated lanes, dedicated right-of-way, mixed in traffic, etc. — depending on where it is built.

“And that’s great because it’s very flexible,” Anderson said. “The problem is, whatever is in this plan then gets negotiated down from there. And so this is the high-water mark. If you don’t put it in the plan now, it’s not going to get better for transit, it’s only going to degrade.”

Dedicated lanes, signal priority and queue jumping are proven approaches to bus transit and are being implemented in Montgomery by the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority with its MetroExtra limited stop bus service, Schwartz said.

About 700 people ride MetroExtra every day on its route on New Hampshire Avenue, and more routes are planned.

“There’s no better option to manage growth in traffic while maintaining economic competitiveness than investing in dedicated lane transit and transit-oriented communities,” Schwartz said.

Historically, the county approach to traffic congestion was to widen roads.

Yet, many routes proposed in the draft transit master plan cannot be widened, Slater said.

“The only thing you are left to do if the road is as wide as it is today, and you are trying to stuff more people down it, is to put people on something that can move more people than a car,” she said.

But to give BRT dedicated lanes north of the Beltway only to let it snarl in the urban traffic for fear that taking a lane could worsen congestion for the cars would defeat BRT’s purpose, she said.

Once built as planned, BRT will be its own advertisement, Slater said.

Drivers sitting in traffic who see buses bypassing the gridlock will consider taking a bus to get to their destination more quickly, she said.

Reduced from the 160-mile network of 20 corridors recommended last May by the Transit Task Force, planning staff have proposed a 79-mile network of 10 corridors, including U.S. 355 north and south, Georgia Avenue north and south, U.S. 29, Veirs Mill Road, Randolph Road, New Hampshire Avenue, University Boulevard and the North Bethesda Transitway.

Montgomery County’s population reaches 1 million

Montgomery County became the first jurisdiction in Maryland with a population of more than one million last year after gaining more than 13,000 people since 2011.

U.S. Census data released this month puts the county’s population at 1,004,709 as of July 2012.

Prince George’s County had the next largest population in the state, with 881,138 people. Kent County had the lowest, with 20,191.

Most of Montgomery’s population can be traced to the fact that there were 13,097 births from 2011 to 2012 and only 5,467 deaths, according to the county planning department.

Also during that time, 8,700 people moved from other countries into the county, and 3,100 moved out.

Migration from the county is a trend county planners attribute to the recovering economy and housing market, which gives people more freedom to sell their homes as they find work elsewhere.

“We’ve planned for our population to increase,” Rose Krasnow, the county’s acting director of planning, said in a statement. “Years ago, we set up tools to preserve our agricultural land and maintain our single-family neighborhoods. More recently we have created many mixed-use, multi-family housing opportunities in our downtowns or near Metro.”

A growing population raises the perennial concern of creating more traffic, but the county has been taking the right steps to mitigate increased congestion, said Stewart Schwartz, executive director of the Coalition for Smarter-Growth, which advocates for walkable, transit-oriented development.

“[The population] makes it more important than ever that the county continue to focus on transit-oriented development and new rapid-transit systems,” Schwartz said.

Schwartz said the proposed Purple Line light-rail system and bus rapid transit systems — in which buses travel in dedicated lanes to avoid traffic — were the right kind of projects for the county.

The alternative is a scattered, suburban population having to use more crowded roads, he said.

The county’s growth rate from 2011 to 2012 was 1.3 percent, lower than the rates in the previous three years, which ranged from 1.6 percent to 1.8 percent, according to planners.

A similar slowing of growth has also occurred in areas such as Prince George’s County and Fairfax County in Virginia, which also have large population bases, said Roberto Ruiz, research director for the Montgomery County Planning Department. Such decreases are inevitable, he said.

“You’re not going to be able to keep up that rate [if] you’re already starting with a big base,” Ruiz said.

Smart growth key to Montgomery County’s future

Montgomery County is implementing a Smart Growth Initiative to build on the area’s strengths in biotechnology and health care in a way that will create mixed-use neighborhoods and walkable new housing developments.

The three places where most of this new construction will occur are the Greater Seneca Science Corridor along Route 28, the White Oak Science Gateway west of Gaithersburg and the White Flint expansion along Rockville Pike. Each project possesses the core elements of walkability, rapid transit options and mixed-use development.

“Montgomery County has made it a point to invest in transit-oriented communities, and the most successful were Bethesda and Silver Spring. In the future, it will be Shady Grove, Rockville and White Flint,” said Stewart Schwartz, executive director of the Coalition for Smarter Growth.

He said the market demand is very strong for development of mixed-use communities around transit. “It’s much stronger than for traditional suburban development,” he added.

Bonnie Casper, the 2012 president of the Greater Capital Area Association of Realtors, said smart growth is the next generation of development after the superfund trend, which involved taking contaminated sites and redeveloping them through mixed-use development to bring commercial and residential areas back to life.

“Smart growth is an extension of that, taking compact urban centers and turning them back into viable areas around transit nodes to avoid the sprawl,” she said. “More urbanized places like Bethesda, Rockville, Kensington, where the population has grown dramatically.”

The Montgomery County Planning Department’s website shows the Greater Seneca Science Corridor along Route 28 includes a major hospital, academic institutions, such as Johns Hopkins University, and private biotechnology companies. It will offer an array of services and amenities for residents, workers and visitors, including connecting destinations by paths and trails and providing opportunities for a range of outdoor experiences.

“There are 60,000 new jobs slated as part of the Shady Grove and Hopkins sites and new housing that will come into the area,” Casper said. “The key is the rapid transit system. It will cost $2 billion to expand the transit nodes to develop a 160-mile system of modern buses that look like subway cars.”

The White Flint project will enhance and expand development that has already occurred along Wisconsin Avenue and Rockville Pike.

“Retail and mixed business are already there, and it will be revamped into more of a mini town center,” Casper said. “There will be condos and townhomes of various sizes.”

The plan calls for 375-square-foot condos with Murphy beds that are the size of a hotel room.

“It’s based on the theory that younger or single people or oven older people will spend less time in their homes,” Casper said. “They will be in the local coffee shop, going to the movies and sitting out on the bench. Kids who have first jobs will be able to afford these.”

Bethesda is undergoing a huge expansion upward, she noted, and there is a tremendous amount of development to feed the needs of the area. A new Harris Teeter is going in, and Casper said it will have a very different look in the future.

Bordered by Route 29, Cherry Hill Road, New Hampshire Avenue and the Prince George’s County line, the White Oak Science Gateway is focused on developing options for a new research and technology node that capitalizes on the growing presence of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and is complemented by mixed-use development.

“White Oak is where the FDA is, and it was developed a while ago,” Casper said. “That’s another area slated for expansion with additional research facilities and also commercial development — not just roads to jobs but mixed-use development.”

Schwartz and Casper agreed there is a critical need to fund Metro’s Purple Line to Silver Spring and Bethesda.

“We need to continue to fund the rehab of our Metro systems and to tie these traditional transit corridors to development,” Schwartz said. “The real news is that the Washington, D.C., region is beginning to lead the nation in offering effective alternatives and personal solutions to congestion — well-planned, walkable, and transit-oriented neighborhoods and centers.”

Over 1,000 Prince George’s Residents Request Placement of New Hospital at Metro Station Petition Presented to County Executive Baker

UPPER MARLBORO – Today, the Coalition for Smarter Growth delivered a petition to Prince George’s County Executive Rushern Baker, urging him to choose a Metro station site for the planned Regional Medical Center. Over 1,000 Prince George’s residents signed the petition. “The petition demonstrates how many people in our county want the new medical center at a convenient Metro site,” said Coalition for Smarter Growth staff representative and Cheverly resident Reba Watkins, who delivered the petition. “As a Prince George’s resident, this issue is important to me. Right now, without a car, I have to go to Bethesda or D.C. for quality, convenient care. We can do better.” The petition adds to growing consensus that the new hospital should be located at a Metro station site.

Arlington is Booming, And Traffic Fantastically Remains at 1970s Levels

Science fiction fans will recognize this plot line. A woman travels into the past, telling her ancestors about her reality in the future, only to be called a lunatic because of the incredible nature of what she is saying.

Anyone who lives and works in 2013 Arlington, Virginia might be met with the same reaction if she were to go back to 1979 and tell someone about the county’s population, employment, and transportation trends.

Arlington’s population and employment have jumped nearly 40 percent over the past three decades. Meanwhile, traffic on major arterials like Wilson and Arlington Boulevards has increased at a much lower rate or even declined.

Nevertheless, according to our latest research (also embedded below), most executives and business managers based in Arlington County think it’s a fantastical notion that the county will meet its goal of capping rush-hour traffic at 2005 levels over the next two decades.

Of course, first these leaders had to learn that Arlington even has this target. Only 11 percent surveyed knew that the county actually intends to keep rush-hour trips and rush-hour vehicle-miles-traveled (VMT) at or below 5 percent growth of their respective 2005 levels by 2030 (PDF; 1 MB). This goal is in place even though Arlington County planners expect that the population will rise by 19 percent and jobs will increase by 42 percent over that same period.

Once business leaders heard about the cap, a majority (61 percent) agreed that keeping traffic near 2005 levels is important to achieve. However, given the growth projections, it’s not surprising that so many in our business community do not think that we can get to our goal. It may be worth reminding them that other jurisdictions have more aggressive targets. San José, California, for one, wants to reduce the VMT within its borders by 40 percent from its 2009 level by 2040.

Arlington County Commuter Services continues to refine the way in which the county government keeps a lid on traffic with the infrastructure already in place. In 2012, ACCS’s outreach work throughout the county shifted 45,000 car trips each work day from a solo-driven car to some other form of transportation. The Silver Line’s opening at the end of the year will give new options for the large numbers of Fairfax County residents who travel into Arlington or through it to Washington D.C.

Yet now is also a time in which many of our region’s transportation visionaries and transit providers are thinking big about the future. The Coalition for Smarter Growth just released a report that catalogues the many existing plans to improve transit across the region in order to get us Thinking Big, Planning Smart, and Metro’s Momentum plan for improvements by 2040 is a expression of what the heart of our region’s transportation success could look like for the next generation.

Clearly, the billions of dollars needed to make these and other investments possible will not appear out of thin air and, as a community, the D.C. region will need to make bold decisions (just as Arlington has by strictly following its transportation vision set out in the 1970s).

Luckily, Arlington’s business community seems to be on board. Seventy-nine percent think that improving the transit system is important. And Arlington’s track record of success and the attitudes found in our survey of business leaders indicate that meeting the county’s traffic goal is realistic after all.

Does your community have an explicit goal to cap traffic? If so, we would like to hear about it, because seeing the state of practice helps us all make the case that taming traffic is, in fact, possible. Just like in science fiction, it only seems crazy because we have not done it yet.

Photo courtesy of Mobility Lab