The first major re-write of Washington’s zoning code since it was established in 1958 is expected to be submitted by the Office of Planning today, ending six years of work and triggering another lengthy public process before the District’s Zoning Commission, which will have the final say on new zoning policies.

The first major re-write of Washington’s zoning code since it was established in 1958 is expected to be submitted by the Office of Planning today, ending six years of work and triggering another lengthy public process before the District’s Zoning Commission, which will have the final say on new zoning policies.

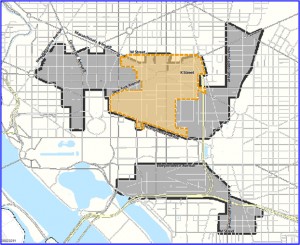

Among the most controversial proposals is the effort to make D.C. less car-dependent by eliminating mandatory off-street parking space minimums in new development in downtown D.C. Planning Director Harriet Tregoning had also proposed to eliminate parking minimums in transit corridors, but recently changed her position to only reduce those minimums.

Tregoning’s change has left advocates on both sides of the debate unhappy.

“We’re encouraged that there’s not going to be an absolute rule that there will be no parking minimums. We think that’s a step in the right direction, but we are still very concerned because the planning director of the District of Columbia has shown her hand. She, for whatever reason, does not believe there is a parking issue throughout much of the District,” said AAA MidAtlantic spokesman Lon Anderson.

“We are disappointed the city has listened to the opposition to progressive reforms and is backing down on the important reform of removing parking minimums in areas that are well served by transit. The proposal would address a number of the biggest problems with parking minimums but we still maintain that parking minimums are not the right approach to building a more affordable, sustainable city,” said Cheryl Cort, the policy director for the Coalition for Smarter Growth.

At the heart of the controversy lies the question: how much parking does a growing, thriving city need as developers continue to erect new housing, office and retail space near Metro stations, in bus corridors, and downtown D.C. The alleged scarcity of parking spaces today is a common complaint of motorists, but those who favor dumping the parking minimums say residents and visitors will have adequate alternatives to automobile ownership, like car-sharing services, Metro rail and bus, and Capital Bikeshare. Smart growth advocates also point out developers will still be able to build parking if the market demands it, but the decision will be left to them, not decided by a mandate.

“We’re building a lot of parking that generates a lot of traffic, undermining the best use of our transit system,” Cort said.

“We spent the last 100 years building our society to be automobile dependent and then to try to change that in a very short period of time is really imposing an awful lot in a region that is still very, very dependent on the automobile,” counters Anderson.

About 38 percent of all D.C. households are car-free, according to U.S. Census data.

Photo courtesy of AP Photo/Michael Dwyer. Copyright 2013 by WMAL.com. All rights reserved.